Blogger: Rachelle Gardner

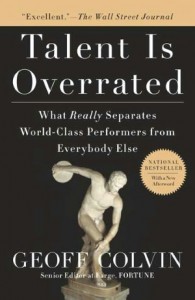

I’ve been studying various philosophies of success and mastery, in an attempt to better understand how to help writers reach their goals. I came across this idea that Talent is Overrated and that, in fact, it is hard work that leads people to master a skill or profession, not any kind of inborn ability.

I’ve written before that there may be a degree of innate talent or aptitude for writing a good book that contributes to a writer’s chances of success. But perhaps I’ve been wrong all this time? I find Geoff Colvin’s theories and his analysis of the research compelling.

He says that it’s not just hard work that makes the difference and leads to greatness. It’s a specific kind of hard work: a regimented and completely consistent practice schedule; tracking and analyzing your performance; and making adjustments as you learn what works and what doesn’t. I admit, it seems hard to apply this kind of structure to writing!

He says that it’s not just hard work that makes the difference and leads to greatness. It’s a specific kind of hard work: a regimented and completely consistent practice schedule; tracking and analyzing your performance; and making adjustments as you learn what works and what doesn’t. I admit, it seems hard to apply this kind of structure to writing!

Colvin further asserts (and I first heard this from Tony Schwartz) that if you’re not actively trying to get better, you are probably getting worse.

He uses the analogy of a golfer going out to hit a bucket of balls. That activity in itself is not, apparently, hard enough work to contribute to improvement, success, and greatness. But the golfer who hits the balls, measures the distance and trajectory of each one, and records information about his swing, his stance, his hand positioning (etc.), analyzing which changes to led to a better result… that golfer is more likely to find success.

Over time, if people are not actively improving, actively incorporating new information and new skills, they will lose ability rather than gain or stay the same.

Hmmm…

- How does this strike you as a writer?

- Is there any way to incorporate this information into your own journey?

- And do you think it’s true that talent is over-rated and hard work is the only thing that matters?

TWEETABLES:

Is talent overrated? Is hard work all that matters? Chime in on the blog. Click to Tweet.

What’s more important – writing talent, or hard work? Click to Tweet.

It’s an interesting theory, but I find it incomplete.

For the golfer (I played competitively as a teenager), a consistent swing can be developed through hard work, but the winning ‘package’ includes so much more – the ability of judge wind and temperature and their effect on a shot, the sense of communion with one’s own physical being, in terms of fatigue and possible pain as a round progresses…the list goes on.

And then there is the mental game, how one handles competition, in a tournament or in one’s own mind.

Many good golfers can’t complete 18 holes with a score commensurate with their ability, because they’ll see a good round developing, get nervous, and start blowing shots.

The mental game is almost all talent, in the form of character and personality. You can’t ‘fix’ a naturally nervous character any more than you can give someone a sense of humour.

Here’s another example – you can turn almost anyone into a good shot with a rifle – on the range. It takes a certain steadiness of hand and sharpness of eye, yes, but the skills are mechanical.

But you can’t make any good shot into a competent sniper, because the nature of the job requires the presence of a completely different set of skills – in ADDITION to the basic skill of the rifleman.

And those skills are a combination of character…and faith. Without the latter, madness is close at hand.

For a writer, my thought would be that the craft can be learned through hard work, but the magic that animates great writing comes from the ability to view people in one’s surroundings with a sympathetic eye, and to translate observed actions, passions, and motivations into character, story, and faith arcs.

You’ve got to have a genuine warmth for people, to create your own and move them through your created world. This, you can’t learn, no matter how hard you work.

(Yes, there are some writers who come across as positively antisocial, but I’ll wager that their curmudgeonly qualities are more a function of shyness and the need for a certain level of self protection that the indication of a truly cold soul. Even Salinger apparently had quite a bit of personal warmth. He was just hobbled by his success when he tried to show it.)

So well expressed, Andrew, that I’m not even going to leave my own comment. I agree completely.

I always wish there was a LIKE button after your posts here.

Wonderful points, Andrew, thank you.

Actually, I would say a nervous character CAN be fixed, but not by anyone but themselves. That’s part of learning to hone your talent and your game.

Andrew, you put into words much of what I was thinking. Of course, no one who feels they have a gift likes hearing anyone could do it if they just worked at it.

While I believe there’s an instinctual, innate aspect to being a good writer — something that can’t be taught, I also agree we should never stop studying the craft. And, honestly, why wouldn’t we want to keep learning? I love to write and to read about writing and to find new ways to write better.

True writers see writing as a passion to pursue not a job to learn.

How about the parable of the “talents”? Bury your talent, and it goes nowhere. Put it to use, and it multiplies. Money, natural ability, learned skill–it doesn’t grow if it’s hidden away.

My one-word for 2015 is “discipline.” Talent without discipline goes nowhere. Discipline without talent may be good but not great.

Maybe discipline is the entry fee for a contest, and talent is the measure on which victory is gained.

Or maybe I have it backwards?

Or the whole thing is so inextricable linked that the analogy is dead in the starting gate.

Shirlee, we have the same word-of-the-year! Surely that’s a type of sisterhood. 🙂

The one-word disciplined writer sisterhood!

Discipline is a great word…especially in growing your talent!:)

OK, a one-word refutation of the thesis. One DREADED word.

Math.

I can speak to this, since I have a doctorate in structural engineering, and had to teach classes that used things like the calculus of variations, special functions (like Bessel functions, which describe the motion of a drumhead), and transforms.

Sure, I could get to the point of teaching it, but there was no way on Earth that I could do meaningful research to which those concepts were vital. My learning was analogous to ‘rote’; I could not see the connections in and ‘flow’ of the mathematical construct that would lead to a robust mathematical model of a physical system.

That ‘seeing’ is pure talent; some liken it to a form of autism. I don’t know, but I’ve seen it in action, and was awed.

To be fair, one could call it a combination of a quick mental response (which can be sharpened) and eidetic memory (which can also, at least to some degree, be learned). But I don’t believe that is the whole thing, because there is also the ability to see a skein of equations that lead from Here to There, a path that may not be as direct as it seems it should be, before it exists in fact.

I don’t like the word talent because it implies some special gift that you either have or don’t, and if you don’t, there’s no point in trying. Writing is two things – a set of skills that can be learned and mastered, and a way of looking at the world, being open to it, learning from it.

John, I think you’ve hit on the most difficult aspect of “talent.” As you said, it implies you either have it or you don’t. And isn’t that true in many cases? The fact that I don’t like it doesn’t make it less true! In any case, I don’t believe it necessarily follows that “there’s no point in trying.” Can we separate our talent or lack thereof, from our willingness to try something, and even work hard at it?

I believe bookstores are full of works by people who don’t necessarily have an inborn “gift” for writing, but nevertheless worked hard and became successful.

I think my point was, it’s best to proceed as if there’s no such thing as “talent.” Because if there is, and you’ve got it, great, and if you don’t, too bad for you. But if you view it as a set of skills that can be learned, and are willing to work hard, you’re halfway home, regardless of what “talent” you may or may not have.

For as long as I’ve been teaching, I’ve said this very thing. Early on I came up with the 10 things you need to succeed as a fiction writer, and talent was #10. And everybody who can string a sentence together has SOME talent. I also know those with huge, innate talent who never made it because they didn’t work at it, or simply gave up when early returns were not what they expected.

I also liken it to golf. Just hitting golf balls isn’t smart work. Hitting, getting instruction, adjusting, then hitting more is working smart.

Which is why I wrote a post called Writing Doesn’t Make You a Better Writer.

Yes Jim, it seems the formula consists of both talent and “directed” hard work. I can’t think of a successful person who did it any other way.

Interesting discussion here today. I love reading the comments. From what I’ve seen, talent is only part of the equation. Hard work, a willingness to learn the craft, the humility to seek critique and input from others? All of these other factors also play into how well a writer creates a story.

The one thing you shared that I hadn’t considered was that, if you’re not actively trying to get better, you’re probably getting worse. It’s not that you’re staying at the same level, you’re getting WORSE. Hmmm. I guess there’s no sitting back on your laurels, or taking a prolonged break.

Great thoughts today, Rachelle!

That’s eye-opening, isn’t it? It really made me think. In what areas of my life am I not actively getting better, and therefore getting worse? Oy.

That whole getting worse thing?

Think of it as a laundry pile, if you aren’t improving the condition of it, it will get worse.

I think hard work goes hand in hand with success, no matter how talented you are. In my opinion though, talent gives you a jump start and greater potential for that success, but with it comes more responsibility (fine-tuning it, allowing it to mature). And if the talented person does nothing to grow their talent and fill their full potential, then their failure is the most devastating.

Yes, I agree talent is hard work. But I believe you have to think smart to succeed as a writer, or even in any profession. Sometimes the talent is there, but if you don’t utilize those skills, then the genius in you will never come to be. Those who have both the talent and the intelligence to make their artistry sell is definitely a role model for all.

Danielle

Rachelle, I think there’s a happy medium between talent and hard work, but without the work or effort expended and improved upon, we might as well kiss opportunity good-bye.

“Happy mediums” are a lovely place to be…for a time. Then reality sets in.

Great food for thought today!

Rachelle, like you, Jim Bell, and others, I liken all this to a sport such as golf or baseball. There’s a certain amount of talent, but there are people with marginal talent who work hard at learning the fundamentals, honing their skills, and being persistent at their work.

Baseball fans need to consider Rangers outfielder Rusty Greer–a man who parlayed a bit of talent and a whole lot of want-to into a major league career.

As we’ve all heard: read the books, write, get critique from a knowledgeable person, rewrite, lather, rinse, repeat. Thanks for sharing.

I, for one, am grateful that hard work plays a large role in writing. Talent is important, but we seem to be given it in varying degrees. I don’t possess the raw talent I’d like to have, but I do my best to make up for that through hard work: studying craft; attending workshops; analyzing the feedback from my agent, editor and writing partners; reading the works of superior writers; trying new techniques; and continually pushing myself to produce better stories. From what I’ve seen as a contest judge reading the work of pre-published writers over the years, I have a hunch I’m not the only one who has had to do more than rather than rely on talent alone. Those of us who work hard can improve and make the best use of the talent we’ve been given. I find that encouraging.

I agree to an extent. I’ve known several people who were tremendously talented in one area or another, but just never had the drive to succeed.

I wrote for a horse racing magazine for twenty-three years. I was very blessed to serve under an editor who believed in nurturing the writer’s voice so each story was easily distinguishable even without a byline. We had a few writers over the years who just never really stood out. Oh, they learned how to research statistics for each race and do interviews and even string together stories that conveyed the facts. They never had any heart in them. Their talent, if there was any, was that knew all the grammar rules and had degrees to prove it. Period.

Talent needs to be nurtured and grown.

Years ago, a ranch had two stallions. Both of them were nice and had some talent, but nothing extraordinary and the ranch was looking for champions. They hired a new manager who was watching the horses work and suggested they train stallion a for roping and stallion b for cutting, which was exactly the opposite of what they had been in training for. They did and voila! The difference in attitude and ability changed remarkably. Both stallions went on to earn championships and became foundation sires. This would not have happened if they had depended solely on persevering and not actually looking at natural talent.

I think anyone can learn to write, but there has to be something inside that makes them a storyteller.

Even if they are a natural born storyteller and they learn how to write correctly, it will be for naught if they don’t persevere, however.

I think we can all agree God gives each and every one of us gifts because He wants us to serve Him and each other in unique ways. We also have the responsibility to be good stewards of the talent God gives us. Cultivate it through practice, improve it through education, and bless others by sharing what we create with it. A river was created to be a river, but if it stops flowing it becomes stagnate.

“There was a tsunami, but most of the believers survived.”

That got your attention, yes?

I have a friend who is a natural born storyteller who could hold a crowd spellbound for half an hour telling the story of how local believers survived the 2004 tsunami in Indonesia.

Talent is getting the attention of the listener, hard work comes in when the storyteller uses his skills with pauses, questions, vocal inflection, eye contact, etc, to keep and hold the attention of the listener.

Much of what I learned about telling a story I learned from listening to great storytellers. I’ve been told I write with increasing intensity, and that I do okay with it, but I learned that by studying those whom I consider to be masters at their craft, both spoken and written.

Talent and craft, and then that special connection between reader and writer that is pure magic. But we as writers have to find our magical connection and keep it alive by always seeking new ways to fire our reader’s desire to come back for more.

I loved this, Jennifer. And yes, there’s stating facts, and then there’s weaving a story with said facts. I’ve learned through reading and listening to masters as well. 🙂

Hmmm…I think he is trying to sell more books with a very clever title! Besides that, I think the truth is in the middle as it often is. Yes, hard work, especially work focused toward achieving a specific goal, is HUGE in attaining mastery. But I think that individuals are gifted in different ways as well, from birth we lean in different directions than those around us. This is a factor as well.

I don’t know. Questions like these almost feel like a waste of time because for a lot of people, there’s no way to know how much talent they have until they’ve done the work.

I’ve read a couple of books on how we often put too much emphasis on talent and not enough on the “hard work” part, so this post resonates with me. As a writer, I want to consider what I’m doing to improve my craft and I think that changes along the way. I joined a critique group last year that has been instrumental in helping me understand areas where my writing is weak and how to correct it. I’ve been writing for more than 10 years and have been a part of other writer’s groups, but I feel like I’m growing in leaps and bounds through my critique group.

I love this post because it affirms the need for us to continue to grow on our writing journey and helps me evaluate how I’m doing that. Thanks Rachelle!

Once I had an editor say, “Julie, it’s not about how talented a writer is. It’s about, how hard are you willing to work?…”

Made me think.

Drive. Hard work. Talent/Gift. No matter how much drive I have or hard work I put into it, I’ll never be a Stephen Hawking. Science interests me, and I wish I knew more and could make the leaps necessary to move scientific knowledge forward. But I don’t and couldn’t if I did. Personally, I think the same thing applies to any field. As for writing, drive and hard work probably put more writers over the top than not. Speaking as a retired English teacher, though, I’ve read a lot of perfectly crafted papers that paled in comparison to others. Without story, craft is framework. Maybe everyone has the gift of story. Maybe it takes something else to bring it out. Maybe my allergies are making me ramble unnecessarily. Either way, this all almost sounds like “Which came first, the chicken or the egg?” Sorry. I’ll go take an allergy pill now.

I’ve been in business over twenty years. I have no talent for numbers, but one cannot run a business without using them, so I do the amount of bookkeeping necessary to hand off accurate files to my accountant. On the other hand, passing off that which I am not good at, frees my time to work more at what I am good at, where my talent actually is.

I believe God gave us our gifts so we would use them, which means working hard at them, not pushing them aside to work extra hard at something for which we have no innate ability.

Given enough time, instruction, and practice, I could do all the accounting myself. But there is only so much time and energy and expending them on something besides the area of my talent, means God’s gift to me is wasted.

It seems to me the key to it all is following God’s leading, to separate what I want from what He wants for me. I could dream of being a writer, but if my gift was singing, wouldn’t I be amiss to pursue writing at the expense of singing?

Well said.

Of course you have to be disciplined and informally watch results, but the methods Geoff lists are a certain personality type. I suspect few writers will do all that measuring. As for talent versus hard work, neither will go far without the other.

I’ll cite two sources who were experts at talent. One is Vince Lombardi, legendary NFL coach, who said, “Practice doesn’t make perfect; perfect practice makes perfect.” His point is that to obtain “perfection,” one must practice what one needs to practice.

The other source is Dr. Daniel Coyle’s “The Talent Code- Greatness isn’t Born, it’s grown, Here’s how.” Coyle defines talent as developing myelin, the sheath surrounding the neural nerves. The thicker the myelin, the greater the talent.

Both of these are about achieving performance “talent,” the ability to perform physical acts, such as golf, violin, guitar, piano, etc.

But to apply this definition to writing seems a stretch. Writing talent does require development, no doubt, and practice is necessary, but where is the “mental myelin” applied? Yet there must be some neurological process that must be mastered in order to become a “gifted” writer.

I have no answer, but I believe that “God given talent” must be like a seed, and like a seed has to be planted and nurtured else it never blooms. That nurturing is hard work, but as Coach Lombardi informs, the hard work must be applied to where the need is. Lotsa luck.

How does this apply to writers and writing? As the comments reflect, we have to keep working at it. What that means to me is that I need to take a multi-pronged approach. For the novel I am knee-deep in, it means keep moving forward while at the same time going back and fixing, tweaking, and re-writing from the beginning. It also means exercises like writing a short story in a different style, voice, or point of view to test new things and keep from getting in a rut. And it means reading award-winning or recognized works in my genre so that I am immersed in the right frame of mind; listening to Selected Shorts and the show about poets (I never appreciated poetry until I came across this program) on NPR; following this blog; and meeting with my writer’s group.

I think I have some small bit of natural ability for writing, but to make it worth reading by others I have to work hard to improve. Sadly, I will never be able to fix my own car.

You know, I like to think that the notion of “talent” is quite similar to the idea of someone having “good taste.” You know, those people wirh an instinctive eye for beauty…who embrace whimsy and flair flawlessly, strut confidently, and seem to have some map the rest of us are missing?

It’s like they have an inborn sense of what works, what doesn’t…they operate on intuition.

I am not saying talent is the full picture, no way. But I do believe God gifts. Of course, He sometimes tasks us with adventures that seem diametrically opposed to our capacities, but that’s just His way of making it uber obvious where the power comes from… 😉

I don’t think it’s talent verses hard work. Desire plays a big part. Whatever you’re trying to excel at, you’ve got to want it. Having talent or putting in a lot of hard work on something you don’t really care about isn’t going to do it without .

Here’s the problem I have with the word “talent.” What is it? Can you point to it? Define it? Test for it? It’s just not a useful concept. I know how much I work – how many hours a day, words a day – I put in. I know what I need to improve, I study, I think I understand people, especially my target audience, and I’m always willing to learn more. I know what I’m not good at. I know where I need to work. I have no idea if any of that is based on talent, because no two people can agree on exactly what it is.

I love this, Rachelle! I’ve worked with so many writers over the years (nearly 50 books I’ve edited have been Traditionally published), and I talk about this a lot when speaking at Literary conferences. You do have to have a thimbleful of talent. But I believe into my soul if you’re compelled to write, you have that. The rest is about skills–and those can be learned. And that’s where the hard, regimented work comes in!

When the tiny seed of Talent is nurtured and blooms, it grows and matures into Passion.

Once something is a Passion, the Motivation is there.

That is why: Passion is no Ordinary Word.

I wonder if being “hard-working” is actually a talent in itself. Are some people born with minds that are wired to persevere?

Just a thought.