In January 2023, I wrote the blog post below to proclaim my favorite read from 2022. I still recall this nonfiction book with fondness and respect–fondness for its exquisite writing and respect for the portrayal of how Indigenous peoples see nature. Eye-opening is another word I would apply to this book and eye-opening.

If you haven’t discovered it yet, let me inroduce you today:

As has been my tradition for several years, I enjoy starting out the new year with reflections on my favorite read in the year before. The books (or book, as is the case this year) don’t have to be releases from that year, and seldom are, actually. They’re simply the books that pleased my heart and mind.

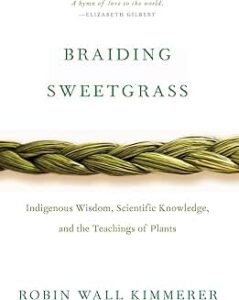

Braiding Sweetgrass Shimmers with Beauty

With that in mind, the big winner of my heart and mind in 2023 is Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer. Don’t let the subtitle put you off, this book is a thing of beauty and the wisdom, knowledge, and teachings are spoonfed to you with a deliciousness that makes you lick the spoon.

The best place to start to grasp what makes Braiding Sweetgrass special is to know who the author is. A botanist, poet, and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, Robin brings a poet’s observant eye to the book and offers us a fragrant bouquet of beauty on every page. Her love and knowledge of plants shines through in such a way that, after reading the book, you’ll never see, for example, a wild, heart-shaped strawberry the same way. Her perspective as a Native American soaks the book in respect for nature and teaches us how to see plants as akin to us in their own kind of personhood, with frailty and strength combined.

Why the Book Was My Favorite Read

Everything about Braiding Sweetgrass made it a favorite read and sang all the right notes for me.

Structure

From the structure of the book, which felt like the author braided the words and ideas together with careful attention, to the way she neatly constructed every chapter was worth admiring. She would start out a chapter with a fetching opening and then draw a perfect circle with her writing as she explored the theme. That circle always closed the loop by ending up where the chapter began. It’s hard to do that well, let alone do it every chapter.

Word Choice

And the pictures her words conveyed were exquisite. Such as, “The ground where I sit with Sitka Grandmother is deep with needles, soft with centuries of humus; the trees are so old that my lifetime compared to theirs is just a bird-song long.”

Or this description of the rainforests of our Northern West Coast:

The canopy is a multi-layered sculpture of vertical complexity from the lowest moss on the forest floor to the wisps of lichen hanging high in the treetops, raggedy and uneven from the gaps produced by centuries of windthrow, disease, and storms. This seeming chaos belies the tight web of interconnections between them all, stitched with filaments of fungi, silk of spiders, and silver threads of water. Alone is a word without meaning in this forest.”

Exploring the landscape after a major snowstorm:

“In the winter brilliance, the only sounds are the rub of my jacket against itself, the soft ploompf of my snowshoes, the rifle-shot crack of trees bursting their hearts in the freezing temperature, and the beating of my own heart…The sky is painfully blue. The snowfields sparkle below like shattered glass. This last storm has sculpted the drifts like surf on a frozen sea….I walk alongside fox tracks, vole tunnels, and a bright-red spatter in the snow framed by the imprint of hawk wings.”

Love of the Land

Her descriptions of different plants convey a profound appreciation for each one.

While mucking about in a lake, observing the plants:

“Mired in weeds, I rested for a bit surrounded by water shield, fragrant water lily, rushes, wild calls, and the eccentric flowers known variously as yellow pond lily, bullhead lily, spatterdock, and brandybottle. That last name, rarely heard, is perhaps most apt, as the yellow flowers sticking up from the dark water emit a sweet alcoholic scent. it made me wish I had brought a bottle of wine.

“Once the showy brandybottle flowers have accomplished their goal of attracting pollinators, they bend below the surface for several weeks, suddenly reclusive while their ovaries swell. When the seeds are mature, the stalks straighten again and lift above the water the fruit–a curiously flask-shaped pod with a brightly colored lid that looks like its namesake, a miniature brandy cask about the size of a shot glass. I’ve never witnessed it myself, but I’m told that the seeds pop dramatically from the pod onto the surface, earning their other name, spatterdock.”

Pick a page, any page, and be prepared to be gobsmacked by the author’s language, knowledge of plants, and love of it all. This is a book to read slowly so as to savor all its richness.

Not a Perfect Book

I did think she presented the ways of the Indigenous people as the solution to our ecological conundrum. And certainly we immigrants haven’t expressed much honor or appreciation for the wealth of our country’s nature. We are consumption-oriented. But I think she isn’t realistic that the answers all lie in the Native Americans’ view of our world. If their population were as large as ours during the time they were caretakers of the land, I wonder what state nature would be in today? Most certainly better than in the hands of us who saw the earth as something to exploit rather than replenish. But her view took on the characteristics of a diatribe when I reached the closing chapters.

The Book’s Publishing History

Braiding Sweetgrass is one of those rare books whose admirers have grown as time goes on rather than readers losing interest. Six years after the book was first published, it made the New York Times bestseller list. It had no big marketing budget when it released, no major reviews to sing its praises. It has remained on that list for three years because its audience can’t help but tell others about this paean to nature.

Ten years after publication, it has sold two million copies.

If you’re searching for a book with masterful writing, passion for the subject, and a different way of seeing all that God has created, then my 2023 favorite read is the next book you should pick up. You’re welcome.

In the this vein, I’d suggest a movie, Te Ata. It’s about a young Chickasaw woman who wanted to be an actress, and became the public voice and ambassador of her people, who happen to be Barb’s people.

I hope it’s okay that I share the following, for this has a personal resonance for me, because Ofhi Tobi, the great white dog who is the spirit guide to the Chickasaw, met me in a near-death experience last week to lead me Home, not that I could stay quite yet, but that I would not fear what comes next.

I am still recovering from what was physically catastrophic; it was also emotionally affecting, in a good way, for I did not realize how many tears were in me.

Tears of gratitude, tears of sorrow, and, if such a thing exists, tears of wonder.

***

I’ve wandered far across the land,

from sea to shining sea,

but still I did not understand

that the land indeed owned me

until the very day I died

and the White Dog led me home,

to where I might lay down my pride,

never more to roam

in search of that elusive

ghost I called Myself;

that image, so obtrusive,

could be placed upon a shelf

and I could take a humble place

at the fireside of tribal grace.

The History of book is what caught my attention most. No instant accolades, but over a period of time, gained the success it was due. Even more interesting, is I know nothing about nature that much or native America, yet I am suddenly drawn in to learn more.

Thanks Janet.

Terrance, I found a deeper understanding of Native Americans from reading this book. I hold profound respect for their connection to all creation. I hope you find reading Braiding Sweetgrass as gratifying an experience as I did.